The remains of the only surviving manuscript concerning the horror that struck Karachi on 30-12-2020 as witnessed firsthand.

Dear Hafeez,

I have news, my friend―dreadful news! Although I am not sure to what extent this matter shall affect you, I feel it my duty to inform you of it nevertheless. Do you remember that classmate, Shafi Rehman, you used to have in the Sukkur IBA University about whom you spoke extensively to me in our dorm room? In my late shift as a paramedic a few months ago, I was summoned to a bungalow in Khairpur, where we found a dead body hanging by the ceiling. He was a young man, and I at once grew curious as to what caused his death. I did my own little investigation and discovered a little diary on his desk. I vigilantly slipped the diary in my coat and left. And after reading the diary that night, I have been ambivalent about what to do with it. I am sure Shafi’s abrupt death must have also provoked your curiosity, and I have attached the diary for you to read too. I remember your admiration for him even though you openly only expressed nothing but contempt for him, and it is because of that I find it only fair that you should also read his last piece of writing. Burn the diary after you read it. You will know why, as I do now, the world is not a place for people like Shafi. You are better suited to this world, I dare say―your stoic composure will always make sure you never succumb to the weakness of human emotions as Shafi did. Tell me, my friend, do you still live alone? It has been months since we last communicated, and I can only hope you have changed your mind about marriage. The life of solitude isn’t for you, Hafeez. You deserve better. Maybe I am wrong about you―you are a lying knave after all. Perhaps you already have your eye set on a girl. If only you could direct me to someone who really knew you! You are an utter mystery. I sometimes think you make yourself so mysterious on purpose―maybe you enjoy watching people speculate about you. Although I know you don’t respect my advice, I shall impart to you some wisdom nevertheless. Stop listening to classical music―it has consumed all your life and what good has it brought you? And what girl will notice you when you spend all your time in your apartment, cut off from the rest of humanity. And what else do you do in there except listen to music?

Take care, my friend. I will be expecting your reply.

Your friend,

Afzal Abbasi

Sitting on the window sill, my legs dangling over the anxious crowd with the distance that five stories could allow between us, I sighed heavily and grinned. I crumpled the letter into a ball, and, with the unread diary, tossed it outside the building.

“What is Shafi to me?” I chuckled ironically. “That naive lad―he should have been born in Ancient Greece and sung dithyrambs with a pedestrian crowd.”

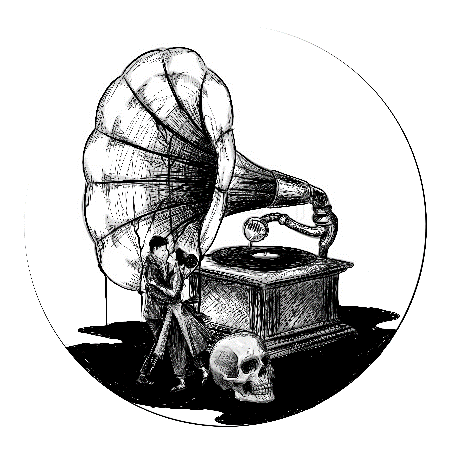

Before I was done peeking outside my window, the horrid sound of crumbling buildings, vapors of dust rising above their ruins, broke my concentration on the most important task at hand. Slapping together the shutters, I walked back to the old cassette player with a mischievous smirk and slowly inserted the cassette for Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony Second Movement while the apartment building periodically trembled with fear. The music followed the gorgeous arrangement of notes put together by my dear deaf Ludwig Van. Dancing alone, I awaited the immortal bastard called death to take me out while the time was still right. Let him come and be disappointed that our journey to oblivion shall be without any fear or even a whimper on my part. I shall have one arm coiled around his neck that would make us seem like two buddies returning back home after a war, I mused. Oh, Dionysus―thou art mine only companion, thou wise character!

The screams of shrieking humans emanated from the alley that my building overlooked. I stopped dancing and went back to the window to take a good look at the hysterical crowd. There were many sprinters among them―and some lay still on the ground being run over by them. The sight was magical, so much so that I suddenly recalled another matter of importance that had escaped my attention. Gazing on the panicking crowd, the music gushing forth behind me, I bit my lip and sighed heavily.

“Would Bushra need me right now? Even if she does, she isn’t going to come to me of her own free will,” I mused. “Perhaps I need to console her now. Damn her! She’d rather die alone than to ask for my help.”

I sprinted to her room. Then, standing before her door, I hunched over my knees, exasperating. I pounded on her door like a drunkard.

“Bushra! Come out and see me.”

“Who’s there?” a voice came from behind the door.

“Who do you think?” I asked, still exasperating. “It’s Santa Claus. Open the door and receive your gift, moron.”

She unbolted the door and faced me.

“Really? You’re gonna call me a moron, Hafeez?”

“What else should I call you―stupid, idiotic, or dumb? Take your pick.”

Her face suddenly changed―a sort of defeat came over it.

“I am very, very sorry, Bushi. I didn’t mean to … I was only worried, you know?” I explained. “Forgive me.”

She remained quiet with her eyes stubbornly fixed on the floor.

“Are you aware that the world seems to be coming to an end, my dear?” I asked.

“Of course. What do you think I am, deaf?” she exclaimed, her eyes still fixed on the floor.

“So why aren’t you screaming the shit out of your lungs and crying, Bushi?”

She suddenly looked up.

“Shhh … quiet,” she whispered, putting a finger to my lips. “I want us to die together.”

“What about music?”

“Don’t worry. I’ve got my favorite piece on the record player.”

That was a relief. She suddenly pulled me inside her apartment. I must admit I was more than a little surprised. A feeling of warm affection started dominating me. I slipped my hand around her waist, and we started dancing inside her apartment. The music of a recording of Pachelbel’s Canon in D played by some pianist bounced back and forth from one wall of her apartment to another, and it set the mood for our impending doom. It wasn’t bad. It was perhaps better suited to the occasion than the Ninth Symphony. Bushra graciously followed my movements, and I do not recall seeing her without an inexplicable grin. Was this her real self? Was this what she had always desired and had finally embraced now that the end was so near?

“Did I ever tell you that Canon in D never struck me as a particularly cheerful piece, Bushi? It always struck me as a piece suited to some tragic drama―it has a tragic sense. Have you noticed that?”

“Not really, no. I―”

“Of course, you didn’t. It’s ironic that it’s played in weddings around the world when it actually should be played as two lovers are committing a double-suicide or something.”

“You mean like Romeo and Juliet?”

“Exactly, Bushi.”

She bit her lip, and a sort of nervousness became visible in her face―fear had overtaken her, but she seemed to be fighting against it.

“Can I ask you something, Hafeez? And if you say yes, you have to be absolutely honest with me. Don’t console me or anything―I am not your responsibility.”

“Yes.”

“I … I want you to tell me if―”

Suddenly a solid chunk of the ceiling that had evidently just been barely holding on to the rest slipped over Bushra and hid her away. I did not stay to see what remained of her. I couldn’t―I still had a lot to do. Now that Bushra was taken care of, I rushed outside the building to join the species that I had without choice or will been a part of. I wished to see whether it was of any worth—to see how they would handle themselves when faced with such an adversity. How many of their superficial constructs would still have any hold over them? I had to check it out. A fatal curiosity was better than a passive submission to death, I decided.

I quickly squeezed myself among the cowards and kept propelling forward, forcibly stroking my arms like swim strokes in order to pave a way to the tower. A hand slapped my back. I turned around. Imran stood, about to be run over by the moving crowd, and I understood that he kept clinging to my shoulder to save himself.

“Imran? Dude, quit yanking my shoulder.”

I did not like him very much; he was a fanatic, and I refused to respect anything that had anything to do with fanaticism. He let go of my shoulder and stood hunched over his knees, exasperating.

“Listen, man, could you hide me somewhere? I don’t wanna die. I can’t die. Please, please come on, I need ya,” he pleaded, with his hands joined together. Then, he started bawling and fell to my knees, begging.

“You disgust me, moron. What’s so bad about dying anyway?”

His face assumed an expression of utter disappointment as if I’d told him I’d been having an affair with his wife for the last twenty years.

“Fine,” he grunted. “Where’s Bushra? I bet she’ll help me. She’s an angel.”

I smiled malignantly.

“Yes, she is an angel. Literally!”

“What do you mean?”

“She’s up there,” I said, pointing to the dark sky. “Probably sipping a cup of wine.”

“What? How? How … could she?”

“We were dancing and this piece of—”

“You were dancing? Now?”

“Yeah, yeah. And guess what? This huge piece of the ceiling fell on her, and she died.”

He suddenly gasped and passed out. I did not have to deal with him, so I started pacing once again through the dense crowd. Frequently, shoulders struck me from behind and front, but I persisted, imagining the scene that supposedly lay ahead. Only a few more minutes and I would be there at the tower, ready to attempt the bold enterprise.

Before I could finally leave the swarm, however, the shrill cry of a little child stopped me in my tracks. I looked in all directions but could not spot it. And then, my eye fell on the ground where I beheld the child being run down by alternating feet in rapid succession. I looked back at the tower, sighing. What was I to do? I did not have any responsibility to this child, did I? As far as I could tell, the whole race of humans had not earned the least bit of my respect and that this infant was merely just one instance of their flawed design. The thought also struck me that maybe it would be better for the child to die right now than to face the heart-wrenching loneliness that it might have to experience if I saved it. Maybe, I was doing it a favor. The intellectual grounds for my decision were hardly doubtable; an overwhelming compulsion soon overtook me, and I rushed to the child and scooped it in my arms, away from the cowards who could not endure facing death, that frightening bastard. Maybe I was a hero at the moment, though I assure you it was not intentional. How could the child, this innocent and pure being, be left subject to a tragedy that it did not understand—much less bring it upon itself?

I suddenly wished I had Bushra by my side. Oh, she would have gladly received this child from my fatal arms and swung her on her own arms, assuring it that everything was going to be alright; the snuggly baby would have smiled and wailed with joy, and Bushra, she would have been crying, I tell you. How could I have just left her like that? How could I have been so cruel and indifferent to her? She deserved better. Kneeling right there in the middle of the alley, a shiny stream of tears dripped down from my face to the baby’s. I did not know how to describe the feeling—it was an ultimate catharsis, the breaking of a cocoon of indifference and coldness, that burst inside me and left me on the brink of insanity. I seemed to be breaking down. I felt a temptation to fall flat on the ground as soon as it cleared and gaze at the clear dark sky, to imagine what oblivion would feel like now that I would have to experience it very soon.

But instead, I decided to go back and make sure I wasn’t mistaken. I sprinted back to my building and reached the first floor, with the baby still oscillating on my arms and crying with ever-increasing intensity. The door to Bushra’s apartment was open. I gave it a slight push with my left foot and entered. The large mound occupying the room hid everything from my view, and I had to pick the rocks and stones up one by one to make sure Bushra was still under there, hopefully breathing. Just as I started, I felt a hand strongly tugging me from behind. I almost fainted in astonishment when I turned around. Bushra stood pale as a ghost, her face smeared in blood, eying me with a fierce hatred such as I had never seen before.

“You son of a bitch! Coward! Thanks a lot for taking off like that!” she said, her eyes moving now to the weight that occupied my arms. “What’s that in your arms?”

“It’s the reason I came back, Bushi. Here,” I outstretched the baby to her. “Hold her.”

She started to weep, the back of her hand mopping the tears off her cheek.

“Where did you find her?”

“In the alley outside. She was being run over to death. I saw her and took her. Do you know who I thought of when I had her in my arms?”

“Who?”

“You.”

“Why?”

“Because I know how much children mean to you. I knew that the sight of a baby would make this disaster trivial. I was right, wasn’t I?”

“Of course, you were. You’re always right, you smart-ass.”

She gracefully looked at the baby and fondled her tiny hands.

“Thank you. Thank you very much.”

“It’s the least I could do for leaving you to die.”

I said it humorously, but it came out morbid.

“I didn’t mean…”

She interrupted. “Nah, it’s okay. Really.”

“Thank you, Bushra.”

“What’re you gonna do now?”

“I have a plan.”

“What plan?”

“It’s … it’s nothing. Trivial, really. Do you wanna join me?”

“Sure. It’s not gonna be dangerous for her, is it?”

“No. I don’t think so.”

“Then lead the way, captain!”

I happily walked out, Bushra strutting behind me. As we came out, the alley was almost empty. You could only see a few homeless guys, their faces buried under their knees. The ground kept shaking. I held Bushra’s hand; I could not lose her this time. We made our way to the tower, and I climbed on top of it while Bushra stayed at the ground, wanting to see my performance. I stood erect, cleared my throat, and began to speak into the microphone.

But before I started, I suddenly felt the absence of the appropriate music. There was a record player just lying beside me. I stuck my hand in my pocket and extracted the cassette that I always carried with me, my favorite piece. I inserted it, and Bach’s Arioso began.

“Ladies and Gentlemen, calm down. I am desirous of your company. Kindly lend me your ears! First, listen carefully to the music. I assure you that your fear of the world ending will have no hold over you.”

As I said this, the hysterical crowd, which had not been paying attention to me so far suddenly turned and concentrated its sea of faces on me.

“Close your eyes, people. Let the music run through you; let your will to life be fed! Let the thirst for the unity of the primordial contradiction be quenched inside you. Recall every pain, every joy, every unutterably small kindness and evil you experienced and done. Love it! Say that you would gladly live it not only once more, but for as many times as you may be blessed with it. Do not hold resentment against your oppressors! Let the substance of your life be the only thing of which you are proud. If you cannot be proud of it, I do not possess any sympathy for you, my brethren. You have wasted your existence. The end is upon us; it is true. I see some of you with scowls on your faces and some confused. And who am I? What do I know? Look at me, all of you! Am I whimpering with fear as you are? Don’t I seem content? I have consummated my life, and I certainly hope you have too. Let’s be valorous! Let us wage war on death, despite knowing we are not destined to triumph. Let us die with solemn dignity! Let us not run away from our fate!”

At this point, the crowd laughed and, pointing their fingers at me, hissed with all the hatred they were capable of extracting from the venom of their own despair. I then turned to look at Bushra. There was a certain radiance that was emanating from her face; she was smiling. A smile that told me all I needed to know, of the tragedy that had been hiding in plain sight. The crowd slowly left and left only Bushra and the sleeping baby standing before the lofty tower, on the silent ground.

I descended and joined them at once, and we silently walked back to the apartment building, her arm locked in mine and the other one holding the clueless infant.

“That was brilliant. I loved it. Especially all that stuff about wanting to live the same life over and over. That brought tears to my eyes, you know.”

“Yeah. They were dumb. You’re enough of an audience for me, Bushi. I hope you know that” I said, eying her with a seductive look. “I didn’t like them anyway. I don’t care about those morons.”

“Except you do care about them. Why else would you go to all that trouble to try to make them die with some dignity?”

“Maybe I’m just vain.”

“Perhaps,” she said. “Do you think I am vain?”

“You?” I chuckled. “You’re about as vain as a peacock.”

“Do you think I should be?”

“Yes. It’ll sure be a national tragedy, nay an international tragedy, if you weren’t.”

“Are you being sarcastic?”

“No.”

“Are you being sarcastic about being sarcastic?”

“Wow, you’re really gonna be a great mother.”

She smirked at me. Around this time, we finally reached our building. We went to her apartment and locked the door behind us. The rest of humanity could now go extinct, for all I cared. She put the baby girl in this crib she always had in her apartment. It had been hers when she’d been an infant, and five years ago, when her mother had died, she had kept it in case she ever had a child of her own. The doctors soon thereafter told her she could never have children. She’d been crying about that on the stairs to my floor when I’d first met her four years ago. I’d sat with her on the steps, while she’d turned her teary face the other way. I’d then put my hand on her shoulder and asked, “What’s wrong, Miss Bushra?”

“Do I know you?”

“I live on the next floor. Remember?”

She had just sort of nodded and swiped her cheeks with the back of her hand.

“What do you want?”

“Hey, hey … what’s wrong?”

“Nothing. Just leave me alone, mister.”

“Come on up to my apartment, I’ll fix you a cup of tea. You’ll feel better.”

“I don’t want to impose.”

“You won’t be imposing. Not at all. That’ll probably be the highlight of my day, trust me. Okay?”

Then she and I had had a soul-warming conversation in my apartment and she’d told me all about the baby. We got to be great friends. So that’s how it was. That’s how we’d come to know each other.

Anyway, she put the baby in the crib, and we sort of talked all night after that, imagining what a future would have been like if it weren’t already too late.

“This is our last night, huh?”

“Probably,” I replied, nodding. “Let’s make it worth it, Bushi.”

“How?”

“You know, Romeo and Juliet style.”

“Double suicide? Are you serious?”

“Yeah, so what if I am?”

“What about her?” she asked, motioning towards the crib.

“Oh. I forgot all about her. You’re right. It’s a stupid idea.”

“No, no. Believe me, I’d do it if it was only us.”

“I get it.”

“You do?”

“Sure.”

For a while, we remained silent. Then she suddenly straightened up in her chair and said, “Listen, there are some things I have been wanting to ask you, but I have no idea how to go about it, you know?”

“Just ask, Bushra. You can ask me anything. Anything at all.”

“Alright. Here it goes,” she said, emptily swallowing. “What do I mean to you?”

“What do you mean?”

“You know what I mean. What are we exactly? Are we friends, lovers, or something else?”

“We are whatever you think we are, Bushi. What do you want us to be?”

“All of them.”

“You got it, ma’am. Anything else?”

“Yeah. What should we name her?”

“The baby? I don’t know. You decide.”

“I want to name her Nimrah after a friend of mine who died a few weeks ago. I think you met her once, do you remember?”

“I don’t think so. Tell me about her, Bushi.”

“She got married to this writer―I don’t remember his name anymore. Anyway, he suddenly just murdered her and abandoned their child. Afsan, I think his name was. He’s in a nut-house now. Can you believe that? And by the way, you met her a year ago when you knocked on my apartment, and she answered, remember? I was out to buy some groceries. She was such an innocent soul―so optimistic and so prone to fancy.”

I smiled.

“That’s what we’ll name her, my dear. I remember her.”

“Are you okay?” she asked, watching me lost in thought.

“Yeah, yeah. It’s just that―”

“Yes? What’s bothering you, Hafeez?”

“I had this rival who killed himself recently. I was just thinking about him.”

“Why did he kill himself, Hafeez?”

“I don’t know, Bushi. I got his diary, but I just threw it away. I didn’t want to know.”

“Why?”

“Because it doesn’t matter, that’s why. I knew him, Bushi―he was always melancholic! He was too sensitive―too feeling. We used to be friends at one time. And there―”

“What do you mean ‘too feeling’?”

“I mean his emotions always had such hold over him that his fortitude and ability to be indifferent was always compromised. And―”

“Why is that a bad thing?”

“It’s a heavy burden, Bushi. It took its toll on him, didn’t it?”

“Is that why you are always insensitive and indifferent?”

“Yes, Bushi.”

“I don’t mean to be offensive, my dear, but―”

“But what? Say it. You think it’s a form of cowardice, don’t you? That I am not courageous enough to plunge myself into the abyss of my emotions. That’s what you were going to say, isn’t it?”

“I know that you’re a cosmic pessimist―that you don’t believe there’s any meaning to any of this. So, why not jump into the abyss of your emotions―if it ultimately doesn’t matter either way?”

“Give me one good reason why I should do that, Bushi?”

“For me.”

“For you?”

“Yes. You said just now that we’re lovers too. You will never know how much you can love me if you don’t jump off that cliff of indifference. You have to feel for me.”

“What if I kill myself eventually as my rival did?”

“Then I’ll die with you. Do you know why I want this? Because if I die, I want you to cry your eyes out―I want you to miss me even though it pains you greatly. I want to mean something to you. I don’t want to be just a piece of biological matter to you! The world only makes sense if you feel―and if you suffer. By renouncing emotions, you’re renouncing suffering. How will your love ever be completely real if you don’t risk suffering by giving reins to your emotions?”

She seemed pleased. She smiled, stared, and held my hand. She squeezed it hard; her eyes also began turning red, a small nexus of veins started becoming quite visible. I’d never seen her smile like that before. Sure, she was creepy as hell when the fancy stuck her but this was different. I took her in my arms, making her rest her head on my chest.

“Can I ask you something?” she asked.

“Of course.” I smiled.

“Why aren’t you afraid of death? Why is it that you’re not even a little bit troubled by the thought that this is our last night alive?”

I pulled her closer to me, pressing her shoulder towards me.

“Music, Bushi. It’s as simple as that.”

“Music?”

“Do you remember when I told you about Aristotle’s theory of catharsis? About how watching tragedy can purge you of certain emotions?”

“Yes, but what has that got to do with music?”

“Music with a tragic sense has the same effect, Bushi, but it’s amplified since music speaks to a part of us that language can never touch. That’s my thesis.”

“I don’t know what that means.”

“It means that music has purged me of all anxiety concerning death. I had the rational justifications long ago, but they weren’t soaked in blood for me. The truths that music has whispered into my ear have been wild, and I have felt them and danced with them for most of my life.”

It was a difficult night, I admit. It was hard to get her to sleep. I had to dissolve a sedative in the glass of water I’d brought her. Throughout the night, earthquakes would shake the ground after every few hours. You would hear a building crumble every once in a while. There’d be screams as well, cries for help―for divine intervention.

As dawn approached, I woke Bushra up. She rubbed her eyelids, and for a minute, she’d forgotten what was going on and what had happened yesterday. Then it all came back to her.

“We survived?” she asked.

“Evidently, my dear. You want to go outside, take a look?”

“Let’s go, Hafeez.”

The alley was quiet as a morgue. As we walked out, Bushra screamed. I didn’t. I merely looked at the pool of blood that ran through the ground. I put my feet inside and entered it. Walking slowly through the swamp, a piece of a limb would hit me from behind or under the blood. There were some heads too if you want to know the truth. I looked back at Bushra and yelled, “Go back inside the building, Bushra! Go!”

She obeyed. As hard as I tried, I could not feel sorry for them, the idiots. I went back to the building and comforted Bushra. She’d been traumatized.

I went back to the Bushra’s apartment, where I found her sitting on the couch, her face buried behind her hands.

“Bushra?”

Silence.

“Bushi? My Bushi―look at me!”

She slowly raised her head and looked at me.

“Yes, Hafeez?” she said, crying.

I went near her and kneeling before her, I took her hands in mine.

“Bushra, I have something I want to ask you.”

A shiver seemed to run through her, and she stopped crying.

“Yes, Hafeez―ask anything, my dear.”

I tightened my grip on her hands.

“In the absurdity of this world, there is no meaning to be found. Nothing makes the death of these people any different from any other day on which they live their meaningless lives. Don’t think about any of this, Bushi! Don’t take any of it seriously―it’s all a comedy, don’t you see? Just laugh at it, darling. And speaking of joy, will you marry me, Bushra Ansari?”

A wide grin appeared on her face as if she had been expecting me to ask her all along.

“Yes, Hafeez. I will marry you.”

Since then, we’ve searched for the other survivors. So far, we haven’t found any. This manuscript that you’re reading is the only one I have left. If you find it, find us. The room for a new dawn has been made my friend and let us live it together. All of you with me and Bushra, that angel. You’d love her. I swear you will. And you will find us out of our minds, laughing and laughing hysterically in some corner at the biggest comedic performance that exists―life.

Leave a Reply